Inlay Confusion, Now in your IDE!

This summer I had the opportunity to help teach the course Introduction to Programming in Rust as a part of Brown University’s Summer@Brown pre-college program. The class was three weeks long and for the first week and a half we exclusively used the online Rust Playground for teaching and assignments. We delayed the use of VS Code — or requiring the use of VS Code — for so long in order to make sure Rust was properly installed on all students’ machines.

The code was so small during that first week that the bells and whistles of an IDE are really unnecessary but knowing how to use an IDE is something we wanted to expose the students to. However, we grossly underestimated how much we needed to teach the students about VS Code. Our thought was “it’s basically the Rust Playground, but you also get code navigation, inlay hints, and you can run a full project.” Win, win, win … right?

In my opinion, Rust has a pretty ugly syntax. There are lots of symbols and punctuation, and although most of the students didn’t have any programming experience, some did have some Python experience. That’s to say that in the first week many students really struggled to remember where semicolons and braces go; they would get into a such a messed up syntactic state that the only way out was for myself or another instructor fix the code. Teaching along the way, of course, but there simply wasn’t enough time for us to let them spin their own wheels on silly problems, like syntax, for too long.

In the second week the number of syntax errors dwindled, but suddenly in the third week they spiked again. And this time the syntax errors were even weirder. For example, below is an example of the kind of syntax errors we’re talking about.

fn fibonacci(n: u32) -> u32 {

if n == 0 {

0

} else if n == 1 {

1

} else {

fibonacci(n: n - 1) + fibonacci(n: n - 2);

// ^^ why? ^^ why again?

}

} fn fibonacci

// ^^^^^^^^^^^ what?

Talking with a student I was trying to understand why they had written fn fibonacci after the function closing brace. Or why there’s a n: when calling the fibonacci function recursively. “Did we accidentally teach them to do that” I panic thought.

After a bit of conversation the student said “these were suggested to me, by CoPilot.” It finally clicked, CoPilot suggestions and LSP hints are presented in the same way: inline with the code. We never told the students about inlay hints, so how would they know the semantic difference between two pieces of grayed-out text presented inline in their editor? Personally, I’ve been using Neovim for the past couple of months and the other instructor uses Rust Rover, so neither of us knew exactly how aggressive the default inlay hints are in VS Code. Here’s a rundown of what you get.

-

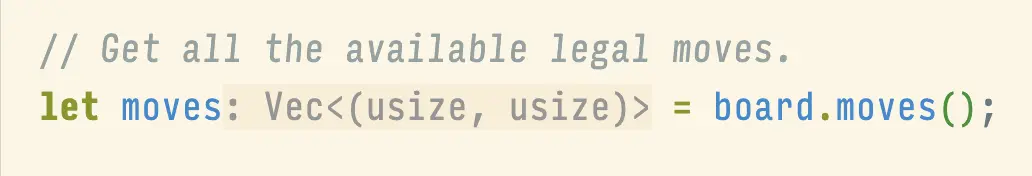

Valid Type Annotations are inlay hints that tell you the type of a variable. Typically, these are on a non-destructuring let binding and are syntactically valid if you want to type them yourself.

An example of a valid type hint in VS Code. The type annotation on the let binding is syntactically valid and something you could write yourself, though you usually wouldn’t.

-

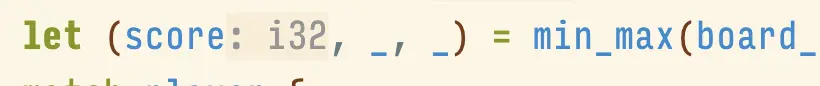

Invalid Type Annotations are inlay hints that tell you the type of a variable, but are not syntactically valid. The most common type — unscientifically measured by my experience — is type hints for destructured let bindings. Also in this category are types that the developer cannot write, like Rust’s “impl trait” type on a let binding.

An example of an invalid type hint in VS Code. This hint is not syntactically valid; writing it yourself would result in a syntax error.

You cannot write type annotations on the destructured variables. If you wanted to annotate the above binding you’d need to do so like this

let (score, _, _): (i32, _, _) = ...;The syntactically valid version of the annotation is a lot more intrusive and verbose. It also gives the developer more information than they likely want. The destructuring syntax makes obvious that it’s a tuple, so that information in the hint would be redundant, and because only the first slot is named,

score, that’s the only type the developer likely cares about. For these reasons the type hint is written syntactically invalid, with the goal of saving space and brain cycles. -

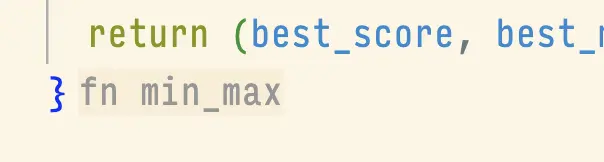

Navigational Hints the last category of hints are to help you, the developer, understand where you are in the code. I call them navigational markers. A good example is writing that a closing brace closes a function, depicted below.

An example of a navigational hint in VS Code. The

fn min_maxtells the developer that this brace closes the body of themin_maxfunction. This is not valid Rust and would result in a syntax error.Brace annotations are not the only navigational hint. I would also consider parameter annotations a navigational hint of sorts.

Where do we go from here?

I am not a fan of inlay hints. I currently use Neovim and previously used Emacs, and in both inlay hints were disabled. I can access the information on demand, because the information is useful when I need it, but I don’t need it 24/7.

As much as I want to say get rid of inlay hints, I think the broader problem is that our IDEs don’t have a way to display rich information. The code, is text. Error tooltips, are text. Inlay hints, are text. CoPilot suggestions, are text. I’m not saying that we should use block editors, I like writing code as text just as much as the next programmer. But not all things should be text, like error messages, which we explored with our Rust trait debugger, Argus.

Maybe hints shouldn’t be textual and maybe, and most likely, CoPilot suggestions shouldn’t be textual and inline with your code. If you disagree, send me an email.